The Letter Is Dead, Long Live the Letter

by Maria Popova

“Everyone writes a letter in the virtual image of his own soul. In every other form of speech it is possible to see the writer’s character, but in none so clearly as in the letter.”

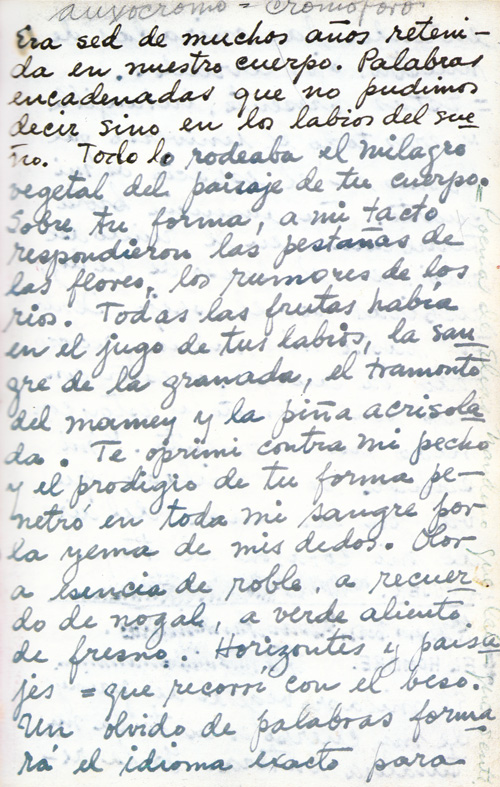

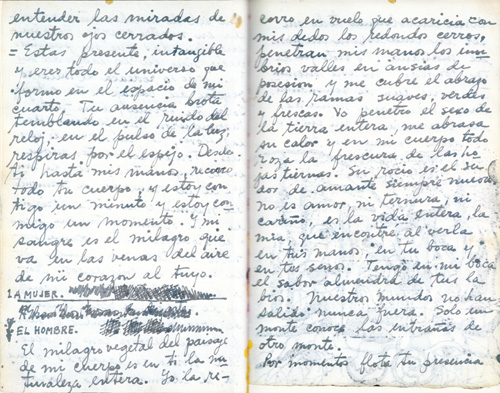

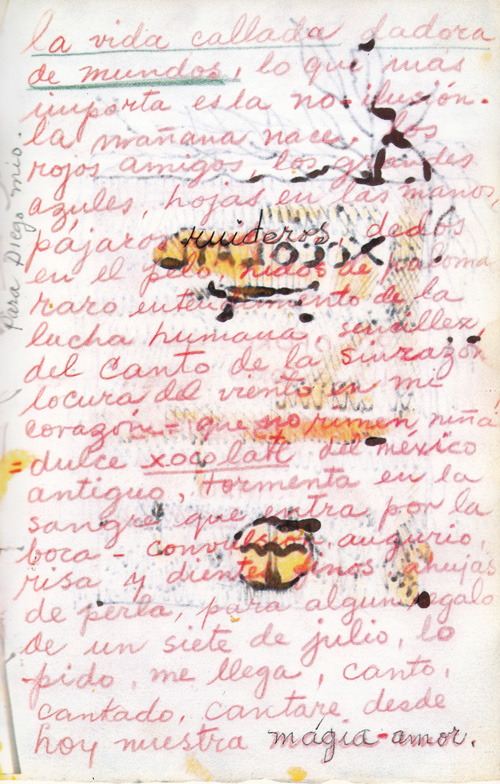

My great-grandfather was an astronomer who used to excitedly awaken his kids in the middle of the night and rush them, barely conscious and begrudging, to his telescope on the roof to observe the occasional cosmic marvel. He raised two sons and two daughters — including my grandmother, after whom I was named — through wartime Bulgaria, and tickled them into that lifelong itch of curiosity and wonder. In his final years, great-grandfather Georgi was living by himself in a small apartment without so much as a landline, hundreds of miles away from my grandmother, who by then was raising a family of her own while working as one of the few female civic engineers in the country. When he fell gravely ill in May of 1984, he wrote my grandmother a letter to tell her about the fatal medical prognosis and mailed it across the country. But he made a mistake — on the envelope, addressed to the correct building, he wrote “apartment 2″ instead of “apartment 5,” so the letter never made it to my grandmother. She got news of her father’s death in early June, from one of her brothers. Six weeks later, she found the letter in the building’s shared mailbox, the ghostly neverland of misdeliveries that residents rarely checked.

My great-grandfather was an astronomer who used to excitedly awaken his kids in the middle of the night and rush them, barely conscious and begrudging, to his telescope on the roof to observe the occasional cosmic marvel. He raised two sons and two daughters — including my grandmother, after whom I was named — through wartime Bulgaria, and tickled them into that lifelong itch of curiosity and wonder. In his final years, great-grandfather Georgi was living by himself in a small apartment without so much as a landline, hundreds of miles away from my grandmother, who by then was raising a family of her own while working as one of the few female civic engineers in the country. When he fell gravely ill in May of 1984, he wrote my grandmother a letter to tell her about the fatal medical prognosis and mailed it across the country. But he made a mistake — on the envelope, addressed to the correct building, he wrote “apartment 2″ instead of “apartment 5,” so the letter never made it to my grandmother. She got news of her father’s death in early June, from one of her brothers. Six weeks later, she found the letter in the building’s shared mailbox, the ghostly neverland of misdeliveries that residents rarely checked.

A week after that, I was born.

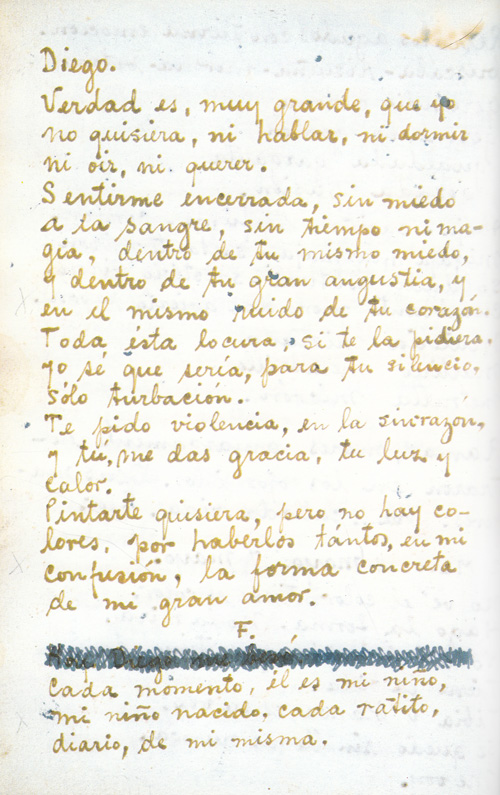

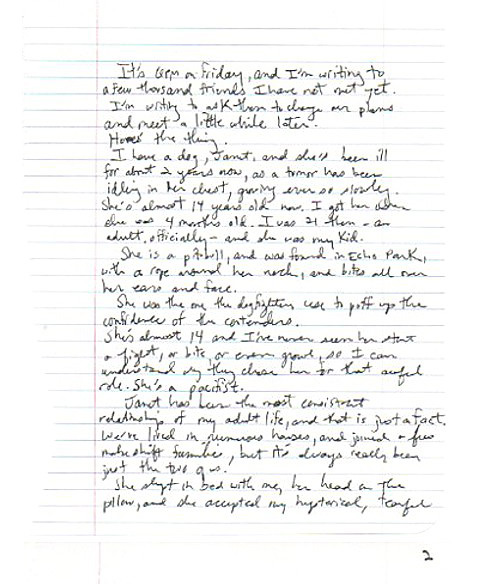

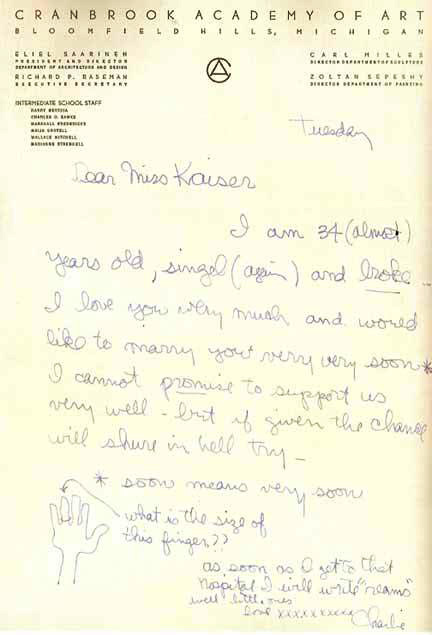

I never met my great-grandfather, whom I imagine I would’ve admired and loved enormously, but my grandmother’s heartbreaking story of postal misfortune, which she only recently shared with me and which pains her to this day, left me newly shaken with the power of so seemingly simple a thing as a letter — a medium that’s always held enormous allure for me, a humble page that blossoms into a grand stage onto which great romances are played out,great wisdom dispensed, and great genius manifested. But what exactly is it about a letter that reaches such depths, and what ineffable, immutable piece of humanity are we losing as the golden age of writing letters sets into the digital horizon?

That’s precisely what Simon Garfield, who has previously explored how our modern obsession with maps was born, seeks to illuminate in To the Letter: A Celebration of the Lost Art of Letter Writing (public library) — a quest to understand what we have lost by replacing letter-writing with email-typing and relinquishing “the post, the envelope, a pen, a slower cerebral whirring, the use of the whole of our hands and not just the tips of our fingers,” considering “the value we place on literacy, good thinking and thinking ahead.”

Garfield writes:

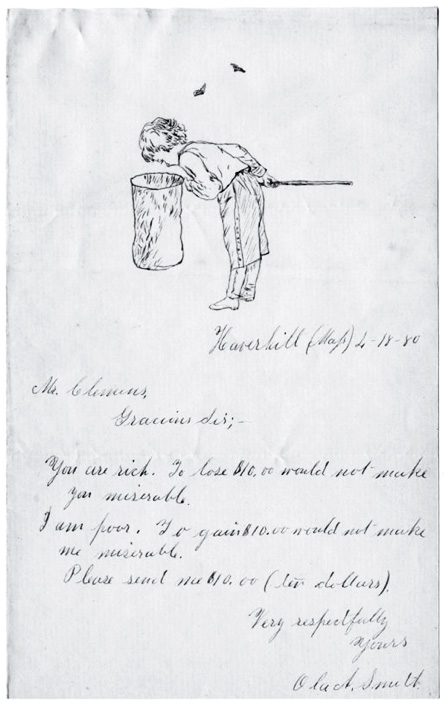

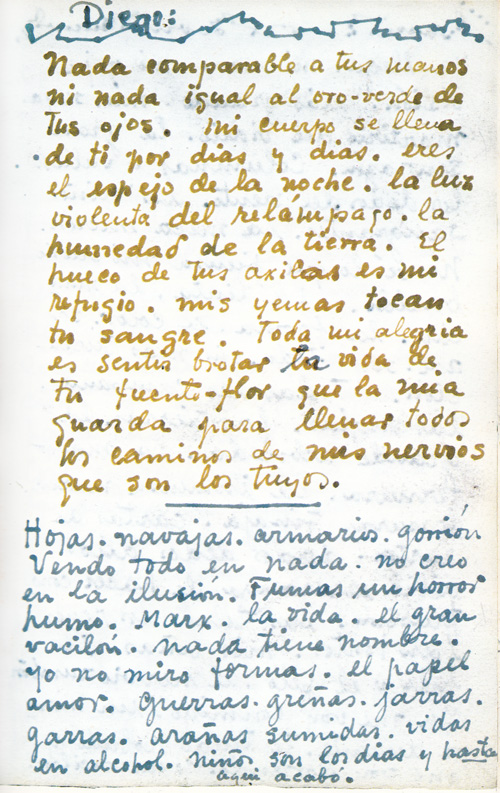

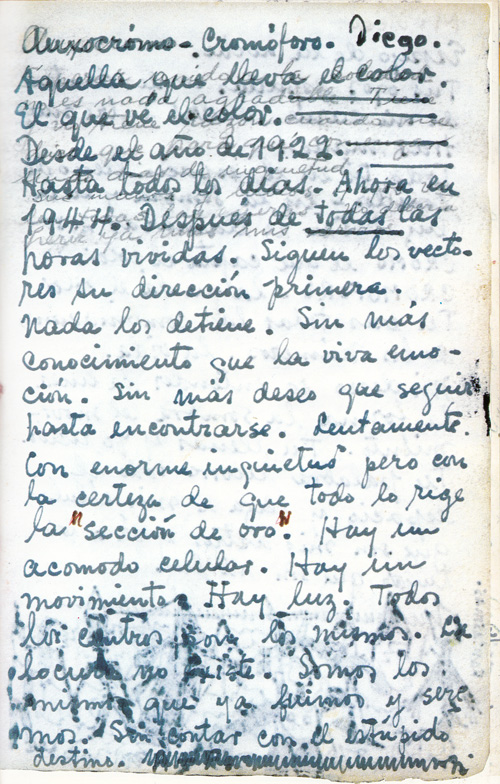

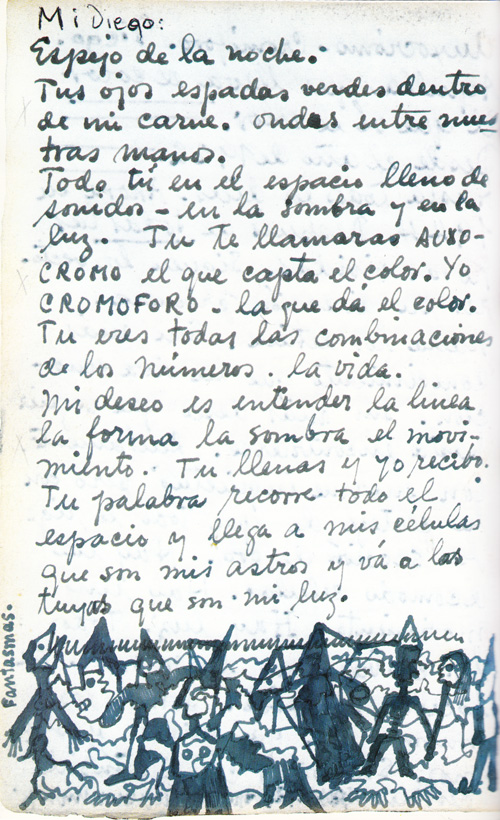

Letters have the power to grant us a larger life. They reveal motivation and deepen understanding. They are evidential. They change lives, and they rewire history. The world once used to run upon their transmission — the lubricant of human interaction and the freefall of ideas, the silent conduit of the worthy and the incidental, the time we were coming for dinner, the account of our marvelous day, the weightiest joys and sorrows of love. It must have seemed impossible that their worth would ever be taken for granted or swept aside. A world without letters would surely be a world without oxygen.

Garfield attributes a good deal of the humanity of the letter — something he so poetically terms its “physical candor and the life-as-she-is-suffered quality” — to the tangibility of how it travels from sender to recipient. Though we know a great more today about how information travels on the internet, Garfield argues for an “intrinsic integrity” that letters hold over other modes of communication and explains:

Some of this has to do with the application of hand to paper, or the rolling of the paper through the typewriter, the effort to get things right first time, the perceptive gathering of purpose. But I think it also has something to do with the mode of transmission, the knowledge of what happens to the letter when sealed. We know where to post it, roughly when it will be collected, the fact that it will be dumped from a bag, sorted, delivered to a van, train or similar, and then the same thing the other end in reverse. We have no idea about where email goes when we hit send. We couldn’t track the journey even if we cared to; in the end, it’s just another vanishing. No one in a stinky brown work coat wearily answers the phone at the dead email office. If it doesn’t arrive we just send it again. But it almost always arrives, with no essence of human journey at all. The ethereal carrier is anonymous and odorless, and carries neither postmark nor scuff nor crease. The woman goes into a box and emerges unblemished. The toil has gone, and with it some of the rewards.

Although much of his argument is premised on these romanticized rewards that stem from the letter’s traditional form — arguments not entirely convincing beyond the automatic sentimentality of nostalgia — Garfield makes his strongest point perhaps inadvertently, in an aside, discussing the letters of 14th-century scholar Petrarch, which used to run over a thousand words. Those letters, Garfield notes, were “not only readable but still worth reading” — and therein lies the bittersweet mesmerism of the letter as a cultural genre: With the ease and rapidity of email, how much of our textual exchanges actually end up being truly worth reading? Rereading?

But the best, most eloquent articulation of just what makes the letter worthy comes from one of Garfield’s ancient-world epistolary champions. Demetrius, who lived sometime between the fourth century B.C. and the fourth century A.D., captured the essence of the perfect letter:

The letter should be a little more formal than the dialogue, since the latter imitates improvised conversation, while the former is written and sent as a kind of gift. . . . The letter should be strong in characterization. Everyone writes a letter in the virtual image of his own soul. In every other form of speech it is possible to see the writer’s character, but in none so clearly as in the letter.

Garfield’s core argument, while anchored a tad too stubbornly and narrowly to the preservation of letters as a medium, speaks powerfully to a broader urgency — the increasingly endangered species of meticulous, thoughtful self-revelation and deep mutual understanding through the written word in the age of reactionary responses and knee-jerk replies. He captures this beautifully:

Great miserabilist that he was, Philip Larkin was spot-on with his famous line from ‘An Arundel Tomb’ … what will survive of us is love. Letters fulfill and safeguard this prophecy. Without letters we risk losing sight of our history, or at least its nuance. The decline and abandonment of letters — the price of progress — will be an immeasurable defeat.

To the Letter goes on to explore the history of letters and the humanity of letter-writing across the millennia, from ancient Greece to the Enlightenment to the invention and advent of the internet, covering the entire spectrum of genres from sales letters to love letters and exploring the intricacies of what makes a perfect letter. Complement it with this fantastic 1876 guide to the art of letter-writing, then revisit some of modern history’s most rereadable letters.